Reality and Depth

Introduction

The style of a serious artist is normally a by-product of trying to deal with something (or a few interlinked things).

The original intention of this essay was briefly to convey, through looking at two or three of my pieces, how one problem has been central to the conception of most of my work: how to embody, materially and metaphorically, the ambiguous relationship between the world in itself and the world we experience. But before I could deal with my response, I first had to convey how I see that relationship.

My subject, then, is the core subject of philosophy - the basic nature of human reality. However my method has allowed me to sidestep the question of whether there is such a thing as a unified self.

I have tried to find a theoretical and practical way out of the limiting art-world interpretation of postmodernism: a simple basis for an art which allows depth without returning to Romanticism: an art which can cope with the idea that there is nothing beyond this world while retaining a precise sense of the spirit.

An earlier version of this essay was printed by the magazine Vertigo. It partly grew out of a paper I had given at a symposium on the poet Wallace Stevens, which concerned the very similar philosophical attitudes and intentions I believe are embodied in his poetry and in my art. The essay consequently extended itself, at its beginning and end, into the more general beliefs and attitudes which have shaped my work.

Of course the conscious concerns of the artist may not be what the art turns out to be about.

Reality and Depth

The world and the mind's world

“As though we reflected back to surfaces the light which emanates from them, the light which, had it passed unopposed, would never have been revealed.” (Henri Bergson)

The central problem for art, now and always, seems to me to be the nature of the relationship between the mind and the world - or I could have said, between imagination and reality. Indeed this seems to be tied up with what makes art art rather than something else. However I do not believe that the mind and the world can ultimately be separated, so to me the word reality already implies that relationship.

This basic problem of reality is my central subject, what I want my work to deal with, as it was for the American poet Wallace Stevens. In a sense my work tries to model basic reality’s essential ambiguity.

Reality is something we experience in the gut rather than the intellect, though what exactly we experience will slowly be modified by what we believe.

For many people the loss of religious faith and the creeping relativism of all beliefs and values has drained the world of the sense of depth which we cannot entirely do without. And art has mirrored this flatness with its own.

"Things merely are" as Stevens wrote. But perhaps it is within our relation to this "being" (and our eventual ceasing to be) that a difficult, open-eyed return to depth might be negotiated.

Surfaces

As someone with an essentially religious temperament I experience modern reality, despite its wide horizons, as impoverished by the loss of the sustaining fictions of faith. This rootlessness is tied up with the modern condition and doesn't seem to me something I have any choice in. I cannot believe simply because it would make me happier to do so. Nor can I look away.

I accept, of course, that many can still find a way to a supernatural faith; though I worry what other awareness some people jettison to give it room.

Nietzsche, who famously pronounced the death of God, did not return authority to man but to the individual human mind. He thus undercut all moral and intellectual authority beyond the isolated creative will and cleared the ground for postmodernism.

Despite these nihilistic philosophical roots, at its cultural heart I feel that postmodernism has become a militant agnosticism about everything. When everything becomes equal we are, ironically, abandoned to believe whatever we can.

Science tried to continue the idea of universal truths but it now seems that, without the authority of God's imagined eye, everything is vulnerable to the collapse into relativism. In response it should be regularly pointed out that relativism should be relative. Science, for example, is not simply another faith.

However, from this general flattening out, many have concluded that authentic depth is no longer possible in genuinely contemporary art; that it is impossible any longer to say anything. We are supposedly left only with irony, surfaces and sensations.

This reading of postmodernism, derived from philosophers such as Baudrillard, has had a grip on the "official" art-world which it has not had, for example, on literature. Despite the pluralism postmodernism seems to sanction, I believe it has effectively tainted some serious art as not quite serious, rather as a linear reading of Modernism sidelined much innovative art of earlier last century.

Of course the art which creatively reflected this flatness often opened up other directions. Instead of depth, Warhol and his followers offered breadth, a liberation of art into other previously despised languages of popular culture: a sort of democracy. However I feel an obligation, as much for my own sake as anyone else’s, to begin to dig new wells. I don’t believe it is enough simply to re-dig old ones.

Reality and imagination

I found my way back into a world with depth, and the possibility of making an art that allowed depth, through the fact that reality is not transparent, that we each experience what Wallace Stevens called a mundo: reality perceived, and thus formed and embellished, through a temperament, a mind. Our reality is full of histories, meanings, mechanisms, rhymes and rhythms, fears and hopes: all the attendants of time expanded outside the present of sensation.

This recognition of reality as the product of an interplay between the world, in itself, and the mind which must imagine it, brought me back, through the frame of my work, to an idea of the spirit.

For philosophers reality has never been transparent, but for us, now that dryads no longer haunt the bare trees, it is less apparent that what we see is not simply Things in Themselves - somewhat as Magritte's picture of a pipe is not a pipe, though a moment's thought will show that reality is more complex than that.

It has been said that all that we have is surfaces, and on one level that is true. However it is equally true that all that we have is interiors - which are our own interior exteriorised. After all, we can only experience experiences - mental events.

It is the coexistence within our consciousness of these two, incompatible ideas of reality (which philosophy knows as the old battle between Realism and Idealism) which I have always tried to deal with and model in my work.

It is a kind of breathing, between the universe and the imagination, between things and their image in us - like the infinite recession between facing mirrors. And this, interestingly, could also be a metaphor for Antonio Damasio's proposed neurological construction of consciousness[1]. A breathing also between now and not now - between being and not being: inspiration and expiration, light and darkness.

The world in itself is unknowable[2] - but at the core of the reality of experience we feel the heft and hardness of a world of things: and it is this which we seize with our hands and with metaphor (e=mc2 for example), and this from which we must fashion a real love.

At the heart of Wallace Stevens' later thought was: "the idea of the possibility of the Supreme Fiction: recognised as a fiction, in which men could propose for themselves a fulfilment"[3]. Perhaps this invented object of spiritual satisfaction, which would become real in the process of artistic creation, was always more an aspiration than a thing: more a journey towards than a destination. But perhaps it is an exaggeration of something more ordinary, that we constantly make meaning for ourselves, bind ourselves to things and ideas and to others without questions or need of the absolute. Indeed we cannot stop ourselves from doing it. Without fictions we cannot conceive of the world.

However, again like Stevens, I want an art (and a reality) that is not just a gratifying fantasy. I want an art which can deal with ordinary reality and does not depart from it. An art that adheres to reality, to the world of Things which Samuel Johnson’s boot rebounded from[4]. But however close we press ourselves to bare reality, the space the imagination must leap over is always there. "The absence of the imagination had itself to be imagined" as Stevens wrote[5].

Much recent art and art theory has taken the proliferation of electronic information sources as the dominant shaper of modern consciousness[6], and I cannot deny that it has affected it, at least in certain parts of the developed world. Events at a distance become part of our here and now. However I do not feel that this has fundamentally changed the basic ontological or even epistemological experience of being. I emphasise experience, rather than philosophical position since it seems to me that art generally side-steps the traditional problems of epistemology[7] because a work of art deals with our experience of reality through another experience of reality. Art has always existed within more than one idea of reality: immediate and mediated.

What the proliferation of disembodied images has done, as John Berger pointed out, is to separate bodies from appearances, the existent from the apparent, so that images have lost much of their weight, as well as their weight of seriousness - of shared witness in the face of physical reality and death - which they in turn gave back to us[8].

The work

I have talked so far about the view of reality that I wanted my art to deal with. But the real problem for any artist is always how these thoughts can be converted into art problems, that is, problems in relation to media.

The materiality is central, but for me the similarities and differences between my works have nothing to do with what they are made out of or how they are physically organised, but come from how they position the viewer in relation to his own reality.

The danger is always of work becoming merely an illustration of ideas. The thoughts have to be thought and then abandoned like seeds in the earth: returned to only to criticise the fruit.

And however close I may feel to Stevens' attitudes and intentions, his poetry cannot help me to make art. Words and matter impinge on reality in quite different ways.

The works

In early work, from 1977, the ambition was narrower but, at its best, not essentially different. The central thread was the invisible or, more precisely, the not-visible: things in various ways known about, but hidden in space or time. These animated what was visible which I kept as plain as possible.

In the early 80s I started to make works assembled from objects from the real world and sometimes slide projections, which seemed like models of the relation of mind to matter, but I became dissatisfied with these. Then a small group of window paintings by Magritte gave me a clue as to how I could structure these works in a new way.

The first is well known and called " La Condition Humaine". It shows a room with a window, with a painting on an easel standing in front of it. The view through the window continues seamlessly across the painting. This is usually seen as an image of consciousness.

I like Magritte, but I don't find this completely satisfying. It is like an illustration of the idea that we picture the world. But the self and matter, the image of the world and the world, cannot be separated, They are a single experience, a mundo.

You could argue that the reality of the paint unifies everything, and that we can stand, in a sense, outside ourselves to think about ourselves. But we cannot stand outside our sense of reality.

His later solution is much more paradoxical and, I think, better. It shows a broken window. The view through it is unbroken yet the view still adheres to the fragments of glass on the floor inside. The world and the imagination make an ambiguous whole.

Despite obvious differences my piece Secret Sea No.1 ( a boat full of water with oars turned inwards to row inside itself) embodies the same metaphor of inside and outside.

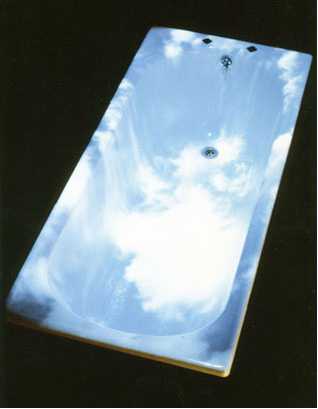

The Bath

The Bath, a real iron bathtub with a slide of the sky projected into it, is another piece conceived in 1984. To me the bath suggests a human body, and by a small shift becomes a substitute for it. Here it contains the sky, the otherness of nature, perhaps the universe. Inside and outside have inverted.

But the projected light is immaterial like thought, like spirit. The bath is heavy, material, an object from the ordinary world. So perhaps it is the world, onto which the mind projects its elaborations, its light.

Despite its simplicity the piece cannot be resolved metaphorically in any simple way. Contradictory interpretations have to coexist. As Stevens wrote, it is “not a choice between but of ”[9].

The piece seems to contain body and mind and world together. For me, and perhaps for others, these pieces are not quite like the experience of seeing the "Other" but something like looking at your own state of being: simultaneously looking in and out; so the light cast on the world is also the inner light.

Despite my readymade materials which pin it to everyday reality (my photographs and recordings are always as direct and artless as possible), the image is vaguely alchemical - the earth dreaming of the sky. Water, the missing element, is here the most important.

The true goal of alchemy was the spiritualisation of matter, which is also Jon Thompson's definition of art[10]. Gold was a metaphor. And necessarily, one with this, was the raising of the spiritual state of the alchemist ("As above, so below"). This sounds like Wallace Stevens, proposing his own fulfilment in the alchemical act of the creation of the poem: lightening the leaden world.

A long series of pieces using inversions of inside and outside followed, including several more which used boats. Sometimes they contained sound, or liquids: water, blood or milk, or even in one case lead waste-pipes.

Imaginary Light

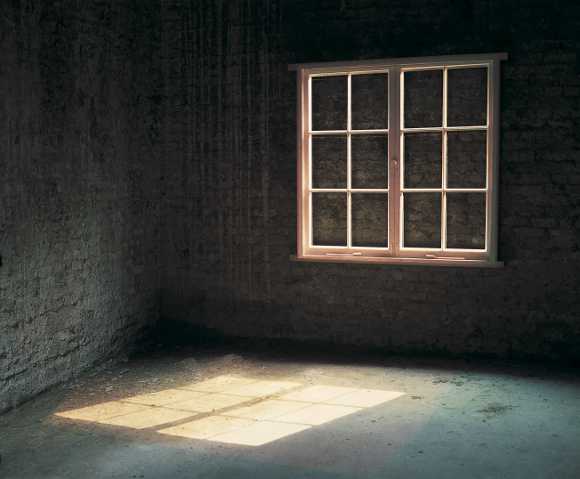

In 1987 I made two works which led to a new series in 2000. In these I used the idea of imagined light - light simultaneously present and absent.

For example "Facing the dark": a window frame hung on a bare brick wall with a slide projected precisely onto its framework and onto the floor, and a little of the wall at the side. No other light. Nothing more.

The slide is projected from above the head of the viewer. Pale sunlight (or perhaps bright moonlight) seems to stream through the window and illuminates the floor. But though the woodwork is lit, where the bright openings should be is darkness: the bare stuff of the wall.

Light is such an old metaphor that we are hardly aware when it is one: enlightenment, awareness, life - and against that: darkness, the night of the soul, the nothingness behind appearance[11].

We look out (and in) at the darkness when we dare, from the small circle lit by our own imagination and hope that the light is not ours only. That it exists without us.

How much we want to believe, to accept transcendence simply. But the projector, the act of projection, is also part of the piece.

This is also Magritte's room, which was once Plato's cave, and could become the closed space of Samuel Beckett's "Endgame": the space of consciousness talking to itself, haunted by remnants. A place where the faith that leaps between imagination and reality, self and others, has atrophied almost to nothing - yet is paradoxically reaffirmed in the luminous act of writing: of bringing into being.

St Augustine wrote about light; and also about inner light, which, in the words of Charles Taylor, "illuminates that space where I am present for myself"[12].

For Augustine the awareness of the inner light becomes an awareness of consciousness as the source of all light. For him, too, the central duality of inner and outer mirrored others: spirit and matter, higher and lower - but also, eternal and temporal, immutable and changing, which for me are frailly echoed in art's attempt to escape time.

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that my work is often interpreted as simply mystical - the light, against reason, shining through the wall, the spirit come down into earth: the moon in a bucket of milk, the skylark's song in a pillow.

The world is ambiguous: why should I insist that my work be otherwise, so long as it contains a little of my truth and my longing. As Don Cupitt[13] once did, I wander the same old circle of stones, scavenging for something that feels like transcendence.

I might echo Stevens on poetry: "Like light it adds nothing, except itself"[14]. But for Augustine, finally all light was God's objective light, both out there, supporting and illuminating matter and, within us, the "Light which lighteth every man that cometh into the world"[15].

Brightness

Art has sometimes been seen as a substitute for religion, and this sounds bathetic and trivial. But perhaps, if like Stevens you see God as the supreme creation of the poets, it would be truer to see both religion and art as reflections of the same way of experiencing life.

Don Cupitt, in trying to work out the basis for a religious way of being that accepts finitude and does not look beyond this world, sees art as exemplary of this way.

He uses the word "brightness" to refer to the world illuminated by consciousness and in particular, quoting Heidegger, illuminated by language[16].

This is close to Stevens' mundo but more radical, and suggests a radiance , a brightness of being, which Stevens sought but which finally remained beyond his reach. And this brightness he sees not just as the illumination of an inner world but of The world - the metaphor spreading both inwards and outwards in the flux of being. Don Cupitt is a thoroughgoing idealist. He has embraced the void behind appearance, which I cannot.

Perhaps by the end what Stevens wanted from his Supreme Fiction was what most people think they have, and Don Cupitt now accepts he cannot - that he could know the bare world in itself, could finally embrace it. But perhaps ultimately Steven's problem, like mine, is less philosophical than a matter of personality.

Being and not being

“For we can unsuppose Heaven and Earth and annihilate the world in our imagination, but the place where they stood will remain behind, and we cannot unsuppose or annihilate that, do what we can.” Thomas Traherne

Now I have moved on again and inverted what I did in those pieces. Instead of creating the illusion of a light source I negate the effect of a real one. However I have, at the same time, returned to the invisible and sometimes to painting, which is my artistic childhood. But this is a kind of anti-painting: instead of starting with nothing and ending with something it starts with something – if only light and shadows – and ends with (almost) nothing.

What I have tried to approach is the limits of reality – the border between being and non-being, the border between matter and thought.

For example, in Trying to imagine not Being a post is lit by a single floodlight.. Its shadow crosses the floor and mysteriously vanishes on the back wall. I have simply (but with great difficulty) painted the rest of the wall the same shade as the darkest part of the shadow. The shadow is still there but you cannot see it.

Trying to imagine not being (2003) (post, floodlight, emulsion paint)

These works balance between being and non-being; with a few props they simultaneously make and try to erase themselves. But they leave a kind of hidden memory, a material ghost that can appear (literally and strangely) in your own shadow.

Some artists today deal, they think, with death, but mostly they just present dead things. The reality of death is an ungraspable disappearance. As Francis Bacon knew, it is the awareness of death which still gives weight to things.

not Finally

Art is not about philosophy, though they share the same source. I have tried, over these few pages, to follow an idea, or an instinct of reality, through into my work. Though I hope that, ultimately, the work escapes everything I might say about it.

I mentioned Stevens' idea of the mundo: reality perceived through an imagination. A work of art, too, is a mundo, which is one reason it speaks to us.

I also suggested a theoretical space for the idea of depth, because reality is neither simply objective or imagined, but somehow both. Behind it is nothing, or perhaps the sublime nothing of buddhists and mystics, but within it are the spaces and sympathies of the self and the nothing the self leaps over to imagine itself - which is itself both everything and nothing.

Surfaces are not all we have - we have both more, and not even that. What we have, briefly, is a life. And within it, close up against it, so that its breath is our breath, we know that the world is real; really real: Stevens' Angel was the angel of reality[17].

If I want these spaces in art, they are something different from the dimension of theory. There is plenty of that in the art world, nor am I wanting less of it. Perhaps what I want is tied to the "grand seriousness" Matthew Collings now feels the lack of, though it doesn't have to be grand and it continues to exist.

Perhaps it needs a multi-valency, a layeredness, an underlying slowness, an inwardness, an implied hinterland. (Also why is the art world so reluctant to acknowledge the core role of metaphor, especially when the work is trying to escape all allusiveness?[18])

Perhaps it involves simply a deep engagement with the nature of being human, which also means, for an artist, with the nature of art. Perhaps it involves an attempt to make something you can't quite come to the end of - something that can contain something of Life that you can't quite come to the end of.

What is important is that the Art World value it again.

How often I read art criticism which tries to fill out something thin, something deliberately flat, rather than trying to find and render down, and say simply, something large and basic and felt. How seldom one hears the word profound. It embarrasses people.

But I believe I am not alone in wanting depth from art again. Ordinary, thoughtful people are grateful when they find it attempted seriously, and this should not be a reason to despise it. The deliberate blankness of Warhol and his successors needed to happen. But now we must find ways, without returning to the past or forgetting the reasons for our disillusionment, of making that difficult place where we can be truthful and yet make a place to stand and sometimes sing.

David Johnson 2005

References

Johnson kicked a large stone, thinking to refute Bishop Berkeley's supposed Idealism (Boswell's: Life of Johnson)

e.g. Jonathan Crary's introduction in Installation art in the new millennium, Thames & Hudson, 2003

Simon Critchley has written about this epistemological side-stepping in relation to Wallace Stevens' "philosophical" poetry in Things merely Are

For the latter in relation to another window painting by Magritte (La Lunette d'approche) see Michael Newman's Some Notes on Nothing and the Silence of Works of Art, Chisenhale Gallery 1995

Writer and founder of The Sea of Faith group, one-time priest and writer/presenter of TV series The Sea of Faith.

This is a revised version of the essay published in Vertigo, Vol 3, No 6. Parts of it derive from a paper given at the Symposium on Wallace Stevens organised by the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Studies, University of London, July 2004