Reviews and articles

The Critics

Imaginary Light

Filled with poetic resonance. The overall effect of Johnson's intelligent and moving show is humbling and thought provoking.

Kathy Kubicki, Art Review

A most striking exhibition. Johnson has something of the magician about him, or the alchemist, and certainly something of the poet.

Simon Morley, The Independent on Sunday

The self is opened up and the cosmos collapses inward. These are haunting essays in matter and light, that speak of absence and death, being and consciousness, and the illusory character of perception and representation.

Wil Bolton, AN magazine

David Johnson invites us on an inner journey at the Roundhouse Crypt to find out what it means to be human. It is weirdly liberating and eerie - like hearing a bird sing in the night. Perhaps his time has come

Helen Smithson, Hampstead and Highgate Express

Johnson's moving rumination on memory and personal loss and its relationship to photography.

Mark Currah, Time Out

Enormously considered - fastidious even - and clever.

Hugh Stoddart, CVA

Ah ! I love your work. The way you speculate stroke create. s/c ! It dances on at least four legs. The dead applaud you too ..... All. all my best wishes. John Berger (letter to the artist)

A sailboat floats with lights burning, the entrance to a deep sea of quietness.

Toyoko Ito, Fogless (translated from Japanese)

Deep and meaningful stuff.

Jamie Woollery, Metro

He consistently elaborates on Magritte's philosophical questioning ... The objects stand in for the human body and are intended to make the viewer look inward. Johnson's success with this effect is illustrated powerfully in what is probably his best-known installation, Ocean (1995), a work that has an almost magical power of attraction.

Johnson's slide installations leave the viewer fascinated. Anyone who senses a nascent yearning for transcendence ... can feel fortunate indeed.

Manfred Heinrich, fotoforum (Article translated from German)

A penetrating and enigmatic corpus of work. We are in the world as much as the world is in us as much as we are in the world. It is this fascinating, subtle and fluctuating interface that Johnson's work persistently explores and tests. Our faith in the veracity of perception is shaken and stirred.

Roy Exley,catalogue essay

I feel honoured to have seen this work.

Stephen Foster, John Hansard Gallery (after visiting the artists studio)

One of the best visual experiences of my life. ... The best exhibition I have ever seen.

Peter Cunningham, London Metropolitan University

Your show was terrific.

Charles Saatchi (letter to the artist)

I feel better about my life now.

Woman on leaving the exhibition

Nave

I left the gallery with a feeling of tranquility and serenity and took up residence on a park bench to savour the moment. I hadn't been so moved by an artwork since seeing Bermondsey artist Richard Wilson's 20:50 in the Saatchi Gallery.

Michael Holland, Southwark News

Returning Light

Twice chosen by the Guardian for their Exhibitions "Pick of the Week".

It is a measure of David Johnson's unusual standing within the art world that he presents installations of highly convincing romanticism. . Johnson mines an obscure seam of absence and otherness, of recurrent archetypal reveries that we can all relate to

Robert Clark, The Guardian

A must-see series of installations by an artist who argues that "the world and the self cannot be separated"; and proves it by a combination of science, poetry and downright magic.

The Leeds Guide

There is a sense that we are observing the tracings and workings of somebody who fills, empties and refills 'mysteries' into the world, where a continuous enquiry and art practice operates as a laboratory for a material and philosophical imagination.

.... he is presenting us with a sensorial and fleeting 'membrane', akin to the idea of the flesh, in-between the visible and invisible, the minute and the vast, the concrete and the immaterial, a transient interworld between life and its gradual or immediate annihilation.

Axis (Asa Andersson)

All the days - Dean Clough, Halifax - 12 May-2 September 2007

David Johnson

All the days, 1999-2005

The mind sees and continues to see objects, while the spirit finds the nest of immensity in an object.1

Sometimes we may be afraid that the reality of something is not going to match up to our anticipations and this was the situation I was in when about to visit David Johnson's retrospective exhibition at Dean Clough in Halifax. I had first become aware of his work through the Axis website and what I could glance from the initial look at the digital thumbnail sized impressions, was the visual promise of a world that was philosophically complex while carrying elements of the magical. After having gone from this mediated online encounter, I was nearing the Dean Clough with a sense of trembling nervousness. Would the work be as alluring as I had imagined, would that philosophical enchantment be present?

Upon entering I found those pieces of work I had glimpsed and dreamt of, scattered over the upstairs galleries and down in the dark and atmospheric arches of the Viaduct theatre. Within the overall challenging and maze-like configuration of the Dean Clough galleries, I had the rare opportunity to experience the fleeting and enigmatic work of David Johnson (the objects and installations date from 1978 to 2007). It felt as if the tiny digital representations that I first spotted on the Axis website, had acted as transitional spaces or portals, such as in fairytales, be they mirrors, holes, or other gateways, whereby we tumble into the depths of the miraculous...

The space of the Viaduct theatre was dark and fairly moist with thick brick walls and the humming of slide-projectors merged with the occasional sound of dripping water hitting the uneven floor. The installed pieces were placed around the centrally located theatre stage and the silhouettes of the ascending rows of chairs were hinted against the selective areas of light. In the Moomin story Moominsummer Madness (1954) by Tove Jansson, the Moomin family encounters a floating theatre where props and other traces are suggestive of the dormancy of past or future events. Similarly, when I entered the Viaduct theatre, the whole space became the world of an unmoored and sleeping theatre but where the fringes were lit up by David's promising light pools, enchanted props and suggestive orchestrations, playing out possible narratives. The margins of the space were providing storage for furniture and other items and this added to the marvel of suddenly identifying one of David's poetically charged manifestations.

Under a beam of light, within an archway, an old wooden rowing boat was filled with dark inky water making up 'All the days' (1999-2005). Within the boat there were white porcelain bowls of varying sizes that slowly sailed the seemingly deep water. The image of a blue sky, with a few clouds, was projected into the bowls and also appeared as a darkish semi-submerged shadow on the surface of the enclosed water. The bowls made a twinkling sound as they grouped together in small formations to then gradually come undone and move on. There was an optic illusion at work where it looked as if the clouds moved; as a viewer I felt as if I was drifting within this world, enabled by the fine grain quality of the slide-projection. In another archway there was a dramatically spotlit old and worn white bathtub. It contained an organic bundle of lead piping where the softness of the lead grey colour, and the bent pipes that emanated from out of the plughole, may have alluded to the physicality of the body. From a distance a glowing window, 'Facing the Dark' (2000), cast an alluring reflection upon the dark floor, and beckoned a closer look. This ethereal window seemed to reveal the view of a brick wall beyond its perimeters. It was puzzling and mesmerizing - there was the paradoxical promise of sunlight coming in through the presumed glass panes yet the immediately 'facing' brick wall would in actuality have blocked out any light.

Facing the Dark, 2000

In 'Untitled (moon)' (1987) a light beam was concentrated into a limited area of a metal bucket and a crescent moon with an iridescent aura seemed to be mirrored in the surface of the milk contained within it. The bucket was at first difficult to spot and only the faintest glow was visible but once the eyes had peered over the edge it was easy to become transfixed. A moment of celestial immensity, where the distant appeared acutely intimate, even if the smallest shake, or attempt to touch the moon by the intervention of the silhouette of a finger, fractured the illusion. Like the portability of the souvenir '50 cc of Paris Air' (1919), a delicate etched pharmaceutical glass phial filled with Parisian air which Marcel Duchamp presented as a gift to an American friend, I developed a desire to keep this moonlit world, to lift the handle and carry the bucket with me.

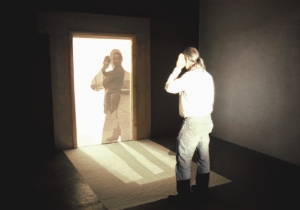

In 'Ghosts (remembering my father)' (2006) there was a blocked yet lit up doorway with a white sheet spread out on the floor in front of it. When walking nearer I became aware that within this concentration of light there was an evanescent image of a small boy held by his father standing on a pier in summer dress. However, parts of the projected image would only be realised by my particular bodily position - as I blanked out rays of light from a second slide the boy and father became visible within my own shadow. The two figures would thus alternate between solitude and togetherness in the presence of the viewer. There was this growing realisation of the unexpected, something that I was sensorially connected to, a recollection in which both memory and the material world slowly coalesced into one. When viewing the work I was in the presence of two small children and this became significant as their height would not blank out the rays and make the faces of the boy and father visible. Even standing on the adjacent white chair would not suffice and an adult's arms were required similar to the held boy in the image. I recognised the intensity of the interrelated states of proximity and distance in relation to processes of longing and how personal memory is becoming rearticulated as we age. A young viewer made the observation that, like the blocked doorway, only fragments of memory can be intuited - once lived through they are in some respects inaccessible to us as we live in a continuous temporal flow...

Ghosts (remembering my father), 2006

She sticks a finger in the water, scattering her reflection; then the circles close up again, a very fine dust settles to the bottom, and her face comes back together: her eyes, nose, mouth, reunited on the jelly of the water.2

The oscillation between presence and absence, the visible and invisible, was also evoked in 'Trying to Imagine not Being' (2003) which showed a plain wooden vertical post that was lit by a spotlight and as a result threw a long shadow across the floor but where it was presumed to hit the wall the shadow seemed to have suddenly and subtly vanished into thin air. There was another piece 'One Day and a Hundred Years' (2006-2007) which further brought up the idea of transience, this time using two sets of digital clocks with LED displays, written instructions, bulbs, and involving computer programming. Through the instruction, 'One Day' invited the viewer to press down a button that would light up the adjacent bulb for the same amount of time the following day. The accompanying part; 'a Hundred Years', would light up for the same duration of time in a hundred years. The first component, with the 24 hour delay, was suggestive of a quite playful moment while the notion that the extension of my gesture and intention will exceed my life span evoked a deeper reflection.

Akin to the legacies of the surrealists, the strategies used by conceptual artists amongst others, several of David's pieces use found, often domestic, utilitarian objects that speak of containment - boats, beds, bath tubs, a pillow, a bucket and a wardrobe. Together with photographs, and displayed drawings showing proposals for potential installations, the work often speak of 'framing' whether formally or metaphorically. By this act of visual distillation, we are brought temporarily closer to something we may otherwise ignore or just accept as habitual. A connection may be made to James Turrell who frames the actual unmediated sky; a square aperture is cut in a roof where the blue atmospheric ether may be seen, or the raindrops or snowflakes may slowly fall into the space gathered by the opening. However, David works with manipulated audio recordings or photographic representations of these elemental worlds which bring at least me into a realm of the mythical. I dream within the composite image (the object and the ephemeral slide-projection or the combined object and sound), and there is a suggestion of an annexation between our inner selves, the wider world and the cosmos; '... the oneiric landscape is not a frame to be filled with impressions, it is a matter which multiplies.' 3 By the expansive act of framing in David's work, I am as a viewer taken on a journey of dreams and associations, it often teases out an emotional response while sometimes being more abstract and interactively playful. In the Korean film, Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter... and Spring by Kim Ki-duk (2003), an old monk raises a young disciple and they live within an intimate floating temple in the middle of a lake. Their sleeping area is only demarcated from the altar by a freestanding door through which they enter and exit although they could easily just skirt around the frame and not have to open the door. Similarly, when engaging with David's work, it is necessary to suspend disbelief and to not become too concerned with the actual technical construction. He offers us small visual baits and if willing, we will be drawn up to the sources of radiance, through the promise of something, such as the beckoning yet deceptive light from the half-open old wardrobe in 'Imaginary Landscape No. 2' (1987-1997) that was placed in an otherwise empty room.

In the Viaduct theatre, and in some of the upper floor galleries, a productive relationship was emanated between the site and the artwork. In 'Secret Sea No. 1' (1984, 1986-1987), an old wooden rowing boat was filled with clear water and with its pair of oar blades reflectively pointing inwards. The boat was positioned upon the mosaic floor in an entry way. The tiled pattern of flowers and leafy ornamentation became suggestive of a garden where the boat with its watery core formed an imaginary pond evocative of the interiority and fluidity of the body.

When engaging with David's work I feel as if observing the tracings and workings of somebody who fills, empties and refills metaphysical 'mysteries' into the world, where a continuous enquiry and art practice operates as a laboratory for a material and philosophical imagination. Gaston Bachelard put this succinctly when he conjoined the phrase: 'dream-physics'.

In the beginning of this text I mentioned how the thumbnail images on the Axis website acted as portals, and after having seen the show (a selection is represented here), I felt as if the actual work invited me to yet another experiential world, an entry point to the world outside. Through taking an imaginary 'star-dive' into 'Ocean' (1995) which presented a night sky with shimmering multi-coloured stars reflected in milk in the bottom of, and across, the interior of an open wooden boat, I surfaced with a heightened sense of the potential miracle world we are guests within.

The walls are exploding. The windows have turned into telescopes. Moons and stars are magnified in this room. The sun hangs over the mantelpiece. I stretch out my hand and reach the corners of the world. The world is bundled up in this room. Beyond the door, where the river is, where the roads are, we shall be.4

The team at Dean Clough should be highly credited for hosting this eloquent show which requires subtle and attentive nursing due to the fragility of some of its materials.

Notes:

- Bachelard, Gaston, (1994), The Poetics of Space, Boston: Beacon Press, p. 190.

- Darrieussecq, Marie, (2001), Breathing Underwater, London: Faber and Faber Limited, p. 81.

- Bachelard, Gaston, (1987), On Poetic Imagination and Reverie, Dallas, Texas: Spring Publications Inc., p. 36.

- Winterson, Jeanette, (1993), Written on the Body, London: Vintage, p. 190.

© Asa Andersson, 2007

Stealing Moonlight

David Johnson's installations at the Roundhouse are filled with poetic resonance. His varied materials include found objects, baths, boats and basins, substances such as blood and milk, slide projections and doorways. The show is a retrospective of work from the early 1980s to the present day. Johnson's sense of the dramatic is evident in the way the work is displayed; it's also explicit in the work itself.

Secret Sea No.2 consists of a small white basin filled with blood, on the surface of which floats a miniature white boat. Lit from above, the solitary basin and the lonely boat are perched on a wooden stool and a plastic sheet is gently draped over the entire assemblage. The invisible is made visible in many of Johnson's installations, and this piece acts as a reminder that the complexity of life and vastness of the universe will never be fully understood. In Untitled (Moon), Johnson has projected a tiny crescent moon onto milk in the bottom of a metal bucket. The viewer is obliged to stoop to examine its contents as if considering a specimen from Johnson's metaphysical laboratory.

The round central space holds two of Johnson's sailing boats (he never uses a boat larger than the human scale). The dark womb-like space envelops them. The Sea of Unknowing is almost filled with dense black fluid and has a small toy boat floating on the heavy, tense surface; a night-light in the boat gives off a tiny glow.

The work 2 Doors (Remembering my father) involves the viewer in a psychological and emotional journey. A half-open door is produced by an illusion of artificial light, as the door leads the audience to a confrontation of a stairway that leads nowhere and is covered with a massive pile of old shoes. Johnson's father was one of the first prisoners to be freed from Belsen.

The overall effect of Johnson's intelligent and moving show is humbling and thought provoking.

Kathy Kubicki, Art Review magazine, April

Charting the dark seas of possibility

In the bowels of the Roundhouse can be found a most striking exhibition, a kind of mini-retrospective of the work of the sculptor and installation artist David Johnson. The 19 pieces exist in pools of light set among the dark and harsh brick tunnels of the space. The journey through the exhibition is a bit like going through the Minotaur's labyrinth, though happily at the centre is no beast but rather two rowing boats. Ocean (1995) comprises one into which we see projected an image of the heavens, in fact the image is partially reflected onto milk, a dense, still surface lying at the boat's bottom. In The Sea of Unknowing (1986) one is filled with dark water on which floats a tiny paper boat holding a small lit candle.

Each of the works presents a kind of logical conundrum that centres on some ambiguity. This registers as a series of expectations thwarted or complicated by the artist's deft use of light, projection, and in one case, the song of a skylark.

This is modern-day Surrealism, but unlike so much other surrealist-influenced contemporary art, his work has a gentle spirituality. I don't know what religious bias informs his work, if any, but it's not difficult to see how it is deeply informed by mystical traditions. Johnson has something of the magician about him, or the alchemist, and certainly something of the poet.

Simon Morley, The Independent on Sunday, March 11

Imaginary Light

The dark cavernous rooms and passageways of the Roundhouse have found themselves home to a series of curious hybrid creations. David Johnson has constructed these sculptures and installations with a lucid fusion of found objects and elemental materials.

A slide projector is used to create chimerical scenes like Imaginary Landscape No.2, in which the reflections of a hazy summer afternoon creeping across Facing the Dark the soft panes of moonlight on the floor seem to shine through a window, whose frame is hung and lit by the slide projected through it onto the floor. This spectral light conjures illusion and artifice, blurring the boundaries of the real and the unreal.

Untitled (Moon) presents the poignant simplicity of a crescent moon projected onto the surface of milk in the bottom of a bucket. The vessel, and the liquid within, act as body signifiers. The idea of containment and reversal - the moon held within the bucket - effects a confusion of inside and outside, self and other, body and world, mind and substance. The self is opened up and the cosmos collapses inward.

In the central chamber of this space, two wooden boats sit on the stone floor. One, titled The Sea of Unknowing, is filled with black ink on which floats a tiny toy boat carrying a nightlight. The other, Ocean, contains milk that appears to reflect the stars, acting as a screen for the projection of a photograph of a clear night sky. Here the inversion is more radical. Boats are designed to keep liquid out, but instead these seem to have swallowed the oceans ands the skies.

These are haunting essays in matter and light, that speak of absence and death, being and consciousness, and the illusory character of perception and representation.

Wil Bolton, AN magazine, April

Underground still lives lead into canyons of the mind

Using objects of our outside lives - beds, baths, boats, windows and doors - conceptual artist David Johnson invites us on an inner journey at the Roundhouse Crypt to find out what it means to be human.

Something rather spooky is happening at the Roundhouse this month. Down in the darkness of the crypt, the artist David Johnson is turning the world inside out.

The Chalk Farm venue is proving an excellent place for shows which explore the darker recesses of our minds, or have a psychological twist to them. And David Johnson's is no exception, for there, in the gloom, pools of light illuminate his contradictory work.

Broadly speaking, he is a conceptualist, but without the glib irony which often accompanies this suggestion.

Born in Highgate he has lived in Gospel Oak for a number of years. Although he left Goldsmiths' College in the early 80s, illness prevented him from producing much work for a number of years. So it is only now that he is emerging into the art world, once again.

And a promising re-emergence it is. He has two solo shows coming up - in Southampton and Nottingham - and Kettle's Yard in Cambridge have expressed an interest.

Perhaps his time has come - we're all a bit bored with smart aleck work these days and Johnson's look a bit deeper than most. Or as he suggests: "It doesn't have to be demonstratively emotional, but this side of the work is important, for (to quote), 'without emotion there is no art'."

It would be impossible to squint in the near-darkness of the undercroft and not feel the touching vulnerability of his works.

There, in the central subterranean space of the building once used to turn locomotives around, are two wooden rowing boats. One (The Sea od Unknowing) is full of water, dyed black. On the inky surface floats a tiny toy boat lit by a single night light. Not only does the use of water within the boat subvert our expectations, but the child's toy adrift on a (relatively)vast sea is a touching metaphor for human experience and endeavour.

Most of his work relates to our individual experience of the world by using object which relate to us: beds, baths, boats, wardrobes, windows and doors.

"I'm interested in the outside world being inside" he says. "That's why I would never use a boat longer than 9ft - it relates to our size and structure, with the ribs and the skin".

Nor does he want to "own the meaning of a work". As he says: "I want things to be able to be read in a number of ways".

Many of the pieces here might on first sight almost look like surrealist one-liners, with their inversions of our expectations. There is a bath with clouds projected onto it; a table glowing in a pitch-black vault apparently lit by an extinguished candle; a wardrobe emitting light.

His use of slide-projections is technically clever, as the shadows play a strong part in the shape of the finished piece.

In an early piece called Cloud, a picture frame appears to hover above a pillow. The pillow is bordered by the shadow cast from the frame. And within the pillow is embedded a speaker emitting the sound of a skylark. The associations are fertile as the objects suggest the outdoors, summer, childhood and; yet here we are in a murky corner, reached through pitch-black rooms and corridors. It is weirdly liberating and eerie - like hearing a bird sing in the night.

Here, the theatrical setting plays a strong part in the show, as the sense of tension you get from wandering around shadowy, cobwebbed, brick corridors on your own works well. You are slightly relieved to see a door installed in a corridor with light coming under it, yet open the door and you are still in the same dark tunnel. It gives a whole new meaning to light at the end of the tunnel.

The idea of light as a sign may have a long established meaning, yet Johnson doesn't see these works as particularly religious. "There is a religious sensibility to them, but without religion, In some sense I see the spirit as a paradise lost. I'm in mourning for this loss" he says.

Hence the little boat drifting on the sea , or a rather gruesome piece called The Effect of Gravity on the Universe. This is in some ways a splendid black joke (and first produced in 1982, long before Damien Hirst cornered the market in jokes about mortality). For contained in a metal box, we are told, is his own weight (64kg) in blood, flesh and bones. Behind the box is a blackboard bearing a ridiculously complicated looking set of equations. This, we are told, is the calculation of the effect of this 64kgs will have on the rate of recession of a distant galaxy. It's so sublimely ridiculous, it's funny.

His work may start to give new meaning to the tired phrase "putting things in perspective".

Helen Smithson, Hampstead and Highgate Express, March 9

SLIDE ART (Illustrated article with short CV and photo of artist.)

Yearning for Transcendence

The world exists, is real. And yet we know that images of the world ultimately originate in our mind. Light is of central importance here, since it mediates our imagining of the world. To grasp the world as it really is - that is the goal of philosophers and spiritual people alike. And their road is transcendence. In his slide installations, English artist David Johnson alludes to this yearning for transcendence in a most impressive way. With imaginary light Johnson stuns the attentive viewer and literally stops him in his tracks.

Transcendence is the overstepping (from Latin transcendere, to overstep) of the boundary of experience; or it can also be simply that which lies beyond experience. In every culture there are people who sense a yearning or desire to overstep this boundary. The inherence of this desire in human nature is what the Americans Maslow and Sutich had in mind when they coined the term "transpersonal psychology" in the 1960s. This perspective embraces the spiritual dimension of the human psyche without commitment to any particular religious form. It is concerned not with dogma but with personal spiritual experiences.

The power of light

Traces of such experiences are found repeatedly in art. Van Gogh, in one of his many letters to his brother Theo, wrote that there was something far more powerful than the Gospel: it was light coming out of the darkness ...

Without a doubt Van Gogh is describing a profound spiritual experience here, for which mystics today use the word "enlightenment". "Light" is an ancient metaphor for knowledge or for the yearning for transcendence.

Other artists, such as the metaphysician Magritte, make transcendence a theme in their works and raise philosophical questions about our habitual perceptions of the world. In his famous painting The Human Condition I (1934), Magritte blends a landscape painting placed on an easel into the landscape visible behind it through a window (picture within a picture), a powerful motif which gives us the spiritual insight that there is really no separation between our inner world and the world around us.

The world exists, and yet we know that the images of the world ultimately originate in our minds. Magritte's work can be seen from two sides as well: Either the world is an image (or dream) projected onto the screen of our consciousness, or it is simply a creation of our mind, which we send out into the world and impose on the existing matter. Both views are true and therefore also inseparable. The "self" and the world exist partly as matter and partly as consciousness.

Thus, it was also Magritte who, through his works, made the most lasting impression on the English artist David Johnson. Johnson is someone who knows what he's doing. In his slide installations, he consistently elaborates on Magritte's philosophical questioning and the yearning for transcendence, for spiritual experience, implicit therein. One of his most impressive works reminiscent of Magritte is Facing the Dark, 2000 (see illustration). Here, too, the image of a window is of central importance. But in contrast to Magritte's painting, Johnson's window is blank. The viewer enters a dark room. On a dark brick wall is a white window with two casements, each with six small rectangular panes. Parts of the mullion and transom are visible in the bright light, which seems to pour onto the floor in front of the window as a light mask. A familiar image, actually, when sunlight shines through windowpanes. But the wall is black, and as soon as the viewer realizes this fact, vacillation sets in. We see the glassless window and where the glass would normally be, the dark wall. The familiar becomes unfamiliar; we take time to pause and reflect. And already the metaphor mentioned earlier comes to mind: "The light that came out of the darkness..." Is there any better transformation?

Projector is invisible

Johnson produces the light image by means of slide projection. The projector, invisible to the viewer at first, is attached to the black ceiling. With it Johnson projects the precise, sharp image of the light mask onto the window and the floor in front of it.

Johnson has dealt intensively with Magritte's philosophical questioning since 1984. Time after time, in his works and slide installations, he seeks to raise awareness in the viewer that there can ultimately be no distinction between subject and object when one looks at the world.

In his installations, the artist is consistent in his approach: His works always have a tangible element (an object, such as a window, bathtub, mattress, boat) and an intangible element (the mere projection of an image of reality such as clouds, stars etc.). With this duality he establishes the relationship between mind and matter. The objects represent the human body and are intended to make the viewer look inward. Johnson's success with this effect is illustrated powerfully in what is probably his best-known slide installation, Ocean (1995), a work that has an almost magical power of attraction for the viewer.

Starry sky in boat

A wooden boat about nine feet long, devoid of seats, lies in a dark area. Approaching the boat, one discerns on its floor a starry sky, which is strangely reflected in the boat. The boat, with its inner life, radiates an incredible, almost meditative calm. Johnson achieves this by projecting a slide of the night sky on a milk surface in the boat. The milk, which covers the floor of the boat, reflects the projected image from its white surface. This "screen", with its warm character, is also an ideal antithesis to the cold starry sky. The viewer cannot help but feel drawn to this work. One reason for this is that the boat, with its exposed ribs, is a strong metaphor for one's own body.

Summary

Johnson's slide installations leave the viewer fascinated. Regardless of the attitude with which one approaches them, a brief pause is inevitable. And anyone who senses a nascent yearning for transcendence, a desire to step over into a world no doubt lost to us but no longer unattainable, can feel fortunate indeed. The work is multifaceted. A visit to his Web site is worthwhile.

Manfred Heinrich in fotoforum July/August 2003

translated by Ann C Sherwin